The Norwegian Consumer Council’s Work on Large Platforms and Data Transmissions from Mobile Apps

harrison grant, political science b.a., the university of north carolina at chapel hill

Overview:

From May 2018, to December 2019, the Norwegian Consumer Council (NCC) published two important reports on data privacy, mobile advertising, and legal compliance under the GDPR. The NCC is a consumer-oriented organization funded by the Norwegian government which promotes consumers’ rights to privacy, security, and balanced contracts. The two reports, entitled “Deceived by Design” and “Out of Control,” (the latter of which was jointly published with a separate technical report), detail multiple experiments conducted by the NCC and independent cybersecurity researchers. Together, these reports demonstrate through multiple mechanisms how third-party code both on the internet and in mobile apps creates privacy and cybersecurity risks to internet users and the US government. Ultimately, the findings detailed in “Out of Control” contributed to a lawsuit filed by the Norwegian Data Protection Authority against the dating app Grindr, which resulted in a fine of $11.7 million for failure to comply with the GDPR. This paper serves as a summary of the reports by the NCC, including background facts, explanations of experimental designs, and key takeaways that the technology policy community ought to examine more closely.

Deceived by Design:

The NCC conducted user trials for this report in May and June of 2018. The report focuses on aspects of platform design for Google, Facebook, and Microsoft’s Windows 10, and attempts to answer the question of whether the design elements are, “in accordance with the principles of data protection by default and data protection by design, and if consent given under these circumstances can be said to be explicit, informed and freely given.”[1] To that end, the NCC examined dark patterns, which are defined as, “exploitative design choices,” that are, “deliberately misleading users through exploitative nudging.”[2] The Council was concerned about whether the presence of dark patterns in the user design and in the word choice of some elements on these platforms might impede a user’s ability to freely give fully informed consent.

The report categorizes areas of user design and wording where dark patterns might exist in the following areas: default settings, ease, framing, rewards/punishments, and forced action. These categories represent different cases during a user’s interaction with Google, Facebook, or Microsoft’s Windows 10 where the NCC was curious about the presence of dark patterns and their impact on user choice. To examine that connection, NCC researchers created fake user accounts and analyzed the five categories of user design and wording to try to understand how design elements might help or impede users from exercising their rights to privacy. Most of the trials focused on Google and Facebook, but some useful data were generated from the trials with Windows 10 as well.

Overall, “Deceived by Design” demonstrates that some inherent platform design elements do impede users’ abilities to exercise their rights to privacy. The default settings for both Google Search and Facebook have selected the least private option, meaning that users would have to go into their privacy settings to opt out of personalized advertising and tracking. Furthermore, the NCC concluded that all three companies attempt to nudge users away from the more private options with confusing wording, more pages to read and click through, and even discouraging button colors and ordering.[3] Likewise, users were consistently faced with take-it-or-leave-it decisions wherein the only two options consisted of accepting data collection and sharing practices or losing complete functionality and access to the platform. Even inside of that reward or punishment framework, the ways that the two choices are framed seem to be designed to nudge users towards acceptance. One such example came from Google Search’s privacy settings as an NCC researcher explored the opt-out options for personalized ads. The text prompt that the user was faced with under the opt-out option read, “You’ll still see ads, but they’ll be less relevant to you.”[4]

Taken together, the NCC concluded from the results of these tests of the examined platforms that users face multiple kinds of exploitative nudging in attempting to exercise their rights to privacy. Facebook and Google do not make it easy to navigate to their privacy settings and make it harder still to freely give fully informed consent to their data collection practices. The NCC claimed that these dark patterns contribute to an “illusion of control.”[5] Under the protections of the GDPR, users tend to feel that they have more control over their data than before. However, the presence of dark patterns raises the difficulty for users to exercise those controls, thus creating an illusion of individual choice. Therefore, the NCC took issue with the notion that users can freely give fully informed consent to these platforms for their default data collection and sharing practices.

Out of Control:

“Out of Control” is the work-product of a much broader study conducted by the NCC and the cybersecurity company mnemonic. The study analyzes data collection and sharing from ten popular mobile applications in the Google Play Store. Researchers from mnemonic purchased Android phones as test devices and used various technical measures to analyze static third-party interactions and dynamic third-party interactions between May and December of 2019. Because of the size of the Android OS market share, and because of the popularity of the apps analyzed by mnemonic, the NCC considers the data generated through this analysis to be indicative of the mobile app ecosystem on Android devices. In combination with other research, this revealing report led to a lawsuit against the dating app Grindr by the Norwegian Data Protection Authority for failure to comply with the GDPR which resulted in a fine of $11.7 million. The principal complaint lodged against Grindr in the lawsuit was that the app was illegally transmitting sensitive information on its users, like sexual orientation and activity, to third parties without obtaining legal consent.

First, here is an overview about the data that the NCC and mnemonic generated from their testing:

· The tested apps included the dating apps Grindr, Happn, OkCupid, and Tinder; the fertility and period tracking apps Clue and MyDays; the makeup app Perfect365; the religious app Muslim: Qibla Finder (which has not been linked to the investigation of the X-Mode data broker); the children’s app My Talking Tom 2; and the keyboard app Wave Keyboard.

· Across the 10 apps, the researchers detected 216 unique domains and 135 unique advertising partners receiving data, of which many of the users of these apps were unaware.

· Throughout the course of testing, the researchers recorded 88,000 data transmissions between apps and third parties.

· The recipients of those transmissions included advertising, mediating, analytics, and core functionality third parties, as well as various kinds of data brokers.

· The content of those transmissions often included highly sensitive user data, such as sexual preferences, intimate sexual details (interests, kinks), religious affiliations, and more.

· The kinds of data transmitted included precise location data, Android advertising ID’s, IP addresses, names, dates of birth, physical addresses, email addresses, and other persistent identifiers.

To conduct their testing, mnemonic purchased Android test devices and downloaded the ten apps. They then performed two different kinds of analyses to identify and analyze data transmissions to various third parties. Mnemonic describes how third parties can receive information from mobile apps through two different channels: through static integration with the Android Application Package (APK), or through dynamic integration with a Software Development Kit (SDK). For the former, mnemonic used tools like Exodus Privacy in order to analyze each app’s third party library. Unpacking this library allowed mnemonic to identify third parties whose tracking capabilities were integrated into the base code of each app.

To test dynamic integration, mnemonic performed traffic analysis. The researchers routed their web traffic through a proxy server, which they owned and housed in the same location as the tests they were performing. The researchers also rooted their test devices, bypassing some encryption techniques in the process in order to be able to analyze the traffic leaving the device. These two things allowed mnemonic to log and decrypt data transmissions from the apps that they were testing in real time. The researchers were able to see to which companies the data was being transmitted, which data was being transmitted, and eventually, to what advertisements those transmissions led. This traffic analysis also revealed the frequency of some of the data transmissions. While frequency varied between apps and third parties, in one example 92 ad requests were made to an advertising party from a single app during just ½ hour of testing.

Of particular importance to our work, the testing of the app Perfecct365 revealed data transmissions to multiple different data brokers. Oracle, Lotome, Dotomai, Nielsen, Adobe, Fysical, Quantcast, Comscore, and Placer (a partner of LiveRamp) were all receiving data transmissions from Perfect365 which included GPS location data and advertising ID’s. In the same way that data sharing between first and third parties for advertising purposes in mobile apps creates cybersecurity risks for internet users, so too does data sharing with data brokers. Obtaining GPS data from in-app users, sometimes at several times per minute (in the case of Fysical), allows brokers to create more detailed profiles of user behavior. These profiles can create national security risks and destabilize fundamental components of how individuals engage in democracies.

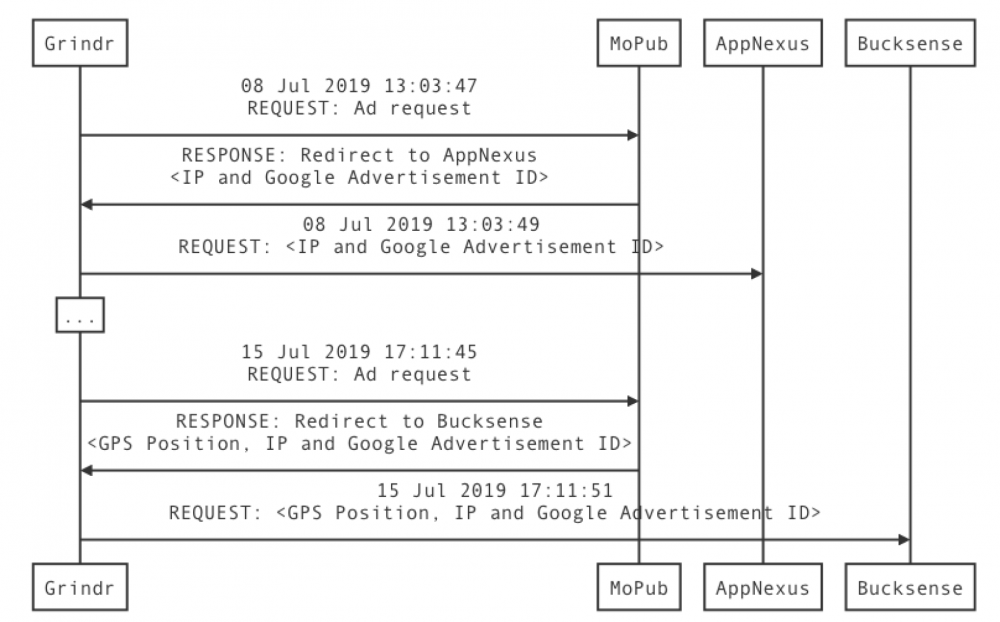

While this report examines ten different apps, the dating app Grindr received the most attention. Grindr was special because it employed an advertising model than none of the other nine apps used. To receive advertising on Grindr, user data was passed from the app to a mediator. In advertising, a mediator is generally a large ad network that directs ad requests to its most appropriate partner. In Grindr’s case, Twitter’s MoPub was the mediator, and was partnered with other large advertiser networks like AppNexus, PubNative, and OpenX. The advertising process is displayed in a diagram at the end of this paper.[6]

After analyzing this advertising model, the NCC and mnemonic concluded that employing a mediator creates heightened cybersecurity risks. In particular, using a mediator prevents a user from understanding to which company their information is being passed. It would be unclear to a user, absent the level of analysis employed by mnemonic, that information transmitted from their use of Grindr to MoPub would lead to their receiving advertisements from another third party (or likely, many third parties). Increasingly, this kind of advertising model creates more opportunities for different third parties to sell the data they receive from MoPub to data brokers. Without appropriate controls on data transfers, this mechanism presents special risks to national security that deserve attention.

“Out of Control” and the Norwegian Consumer Council are widely known for their aid in the lawsuit filed against Grindr. The Norwegian Data Protection Authority sued the app for illegal data transmissions including sensitive user information. The arguments from the Norwegian authority included an emphasis on bundled consent, the practice of third parties claiming their own legal basis to user data because that user has consented to collection and use of their data with first parties.

While significant and nuanced, the takeaways from these reports should not be limited to their application to the case against Grindr. The findings generated by this work indicate systemic problems with third party code and in the online advertising ecosystem, such as large mobile apps sharing sensitive user data widely and opaquely with third parties. The following section describes some of the main conclusions that can be drawn from these two reports.

1.) The title of Deceived by Design is appropriate — big platforms are not designed to be privacy-first. Despite the newfound abilities for users in the EU to take control of their data under GDPR, those controls are weakened by baked-in dark patterns which deter users from finding opt-out settings, and which gatekeep users from engaging with platforms if they do choose to opt out.

2.) Data sensitivity is a key variable — Sensitive data can be used to profile individuals and/or target them with selective information. This data can also be leveraged by foreign nation-states to harm the individuals to whom the data relates, such as in countries where homosexuality is illegal or for the purpose of blackmail. In a related article, Duke University Privacy and Democracy researchers Justin Sherman and Kamran Kara-Pabani describe how actions taken by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) against Chinese investment into Grindr for the sake of national security have not adequately addressed the issue of US consumer information flowing to foreign nation-states deemed national security risks. The continued sharing of sensitive information on US consumers to multiple third parties, and the lack of transparency and controls related to those transmissions, is a strong example of how the current architecture of mobile advertising fosters a dangerously open environment whereby the only barriers to entry are economic. This environment still allows foreign nation-states to access consumer data — it is simply a matter of finding the right supplier.

3.) Data brokers can integrate along the whole AdTech supply chain — From previous work, we know that data brokers purchase or scrape data on consumers from many sources. One of those sources is from first parties themselves — data brokers purchase first-party data in order to understand the individuals that visited that domain. This allows them to build audience segments, which they can then sell or onboard for advertisers and marketers to increase targeting granularity. Increasingly, this report demonstrates that data brokers can obtain data in much the same way from first-party apps. For apps in particular, one key issue is that the granularity of location data received by brokers from mobile apps might be more specific than the data received from a different kind of device (e.g. a laptop), as individuals tend to bring their smartphones with them wherever they go.

4.) Ad mediation as a portal to uncontrolled data sharing — Grindr’s use of MoPub as an ad mediator creates an environment of free-flowing data transmissions to hundreds of other companies. Under current privacy policies, users would have to opt out of data collection from each of the companies that MoPub shares with, a difficult and potentially impossible task. Furthermore, should a user simply opt out of data collection with MoPub, all of the partners in MoPub’s ad network retain access to that user’s data, rendering the request to opt out much less effective.

5.) This is a trust-based system with few incentives to be trustworthy — To demonstrate this conclusion, consider the following example: in order to opt out of personalized advertising and all the tracking that comes with it, many of the apps in the “Out of Control” study direct the user to

their device settings. On Android devices, there are privacy settings that users can change to opt out of personalized ads across all the apps on their devices. However, data transmissions from Grindr to MoPub, and then to multiple advertising partners, demonstrate that opting out of personalized ads has little effect on the data that is transmitted from the app to many other third parties. In a sample data transmission, the advertising ID, IP address, GPS location, and other device metadata were communicated to these advertisers when the user of the test device had both opted in and opted out of personalized ads through the device. The only difference in the information received was a status marker that read “limit_tracking”: true or “limit_tracking”: false.[7] It is up to the discretion of the advertiser to decide to use user data depending upon the user’s displayed preference, but there are no protections for the data communicated to third parties regardless of opt-in or opt-out status.

[1] “Deceived by Design,” 4.

[2] Ibid., 7.

[3] Ibid., 22.

[4] Ibid., 24.

[5] Ibid., 31.

[6] “Out of Control Technical Report,” 26.

[7] Ibid., 67.